Choose Section

KLINGSPOR's Coated Abrasives

Coated abrasives consist of the following components:

An abrasive grain attached to the backing material (i.e., cloth, paper, cotton, polyester) held on with a bonding agent (glue, resin).

We will start by taking each of these components: grain, backing & bond.

GRAIN

There are 4 common types of grains in regular coated abrasives.

ALUMINUM OXIDE (AO)

AO is formed by combining bauxite and other materials, and firing them in an electric furnace. The resultant mass is crushed, and the pieces sifted through successively finer screens to assign a grit size (CAMI grading). When crushed, the resulting pieces are naturally pyramidal. Due to the shape and the strength of the materials used in its making, AO is a very durable grain. The grain is worn down during use, sanding finer the longer it's used.

Theoretically, you can start at 80 grit, and after you've worked the abrasive for a while, you'll be sanding more like 100 or 120 grit. Users take advantage of this characteristic by using the belts on multiple machines or applications. For instance, if you have two wide belt machines doing intermediate and finish sanding, respectively, you may use a 120 belt on the first machine to do your intermediate sanding. When the cut for that application is no longer as sharp, the belt can be moved to the 150 grit machine and used there till the cut for that application is no longer sufficient, ensuring you get the most production and the full value for the belt you purchased.

As stated above, AO is adamant and durable, and is used on bare wood, most metals (especially steel), leather, etc. It is a tremendous general-purpose grain and probably the most, common grain seen today.

SILICON CARBIDE (SC)

SiC combines pure white silica sand and coke, a by-product of coal production. These materials are combined by melting in an electric furnace, crushing the results, and sifting the particles through screens to get grit grading. SiC grains are icicle-shaped with highly sharp points and narrow grain bodies. Therefore, it fractures when pressure is applied to the tip of this grain. It is second only to diamond in hardness but is very brittle due to the narrow grain body. This characteristic is referred to as “friability”.

The benefit of friability is that a sharp edge is always against your workpiece, providing remarkably consistent finishing ability. Because of the lack of grain body strength, which allows this grain to fracture with hand pressure, its life is less compared to AO or other grains. This is why when you see SiC, it's generally in finishing-type operations where the pressure required for working is lower than it would be in removal grits.

Materials typically sanded or ground with SiC would include glass, plastic, rubber, paint varnish, lacquer, and sealers. It may occasionally be seen in sanding on extremely soft woods like Ponderosa Pine, but we recommend open- coat AO instead, as the life would be much better.

ALUMINA ZIRCONIA (AZ)

AZ is a grain that takes the best characteristics of AO and SiC to create one very durable yet friable grain. Its main ingredient is bauxite, just like AO. It is friable like SiC, but machine pressure is required to crack the AZ grain, whereas the SiC grain will fracture under simple hand pressure. Failure to achieve sufficient pressure to crack the AZ grain will result in the glazing of the abrasive grain and reduced life.

The best of both worlds, this grain provides you with a consistently sharp edge on the workpiece and extended life. It is commonly seen anywhere that high removal rates and time are factors, including planing of wood, heavy grinding of metal, and other dimensioning-type applications. It is normally mounted on heavier paper or cloth backings, and the grain itself is 15% – 40% more expensive to produce, so using it in the removal grits, 24 – 60, is where you will achieve more bang for your buck.

CERAMICS

There are several different types of ceramic materials, including ceramic AO, ceramic AZ, and what is referred to as full ratio ceramic. Ceramic combines bauxite, just like regular AO, with other materials in a chemical bonding process. This chemical bonding results in raw grain that is very porous and coral-like in appearance. The full ratio would be the strongest, the ceramic AZ would be next in strength, and the ceramic AO would fall last. Of course, the higher the pure ceramic content the more expensive the material.

Ceramics were created for rough grinding on metal but have crossed over into many other areas where sanding is done. But keep in mind you'll get the most value for your dollar using them in the grits where removal or dimensioning work is being performed and then using regular AO or SiC for the more intermediate and finishing grits.

DID YOU KNOW?

Natural grain colors are:

Aluminum Oxide – brown, pink, white

Silicon Carbide – black

Alumina Zirconia – blue, blue/gray

Ceramic - white

Abrasive manufacturers can make their product any color they choose simply by adding dye to the size coat in the making process. Therefore, you should not rely on grain color to inform you of grain type. Also, adding stearates and lubricants can make it hard to tell the original grain color. Always choose a grain based on the application and the machinery involved.

BACKINGS

The second component we'll address is backings. There are 3 basic categories of backings.

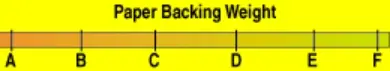

PAPER

Paper backings are available in different weights or thicknesses using the designations A (the lightest weight) through F (the heaviest weight). Lightweight papers A-C are commonly used for power sanding with sheets or discs or hand sanding. The heavier weights (D, E & F) may be seen in sheets or discs for power sanding, or in the case of the E & F weights for belt materials. Only the E & F weight products are considered heavy enough to be belt materials. Some parameters that need to be met before considering a paper belt are:

- Work must be dry. The waterproof papers we have are all A/C weights, and, therefore unsuitable for belts.

- Work must be flat. Paper will not follow a contour easily and is more likely to crease, kink or tear on contoured work than cloth.

- Work should be limited to grits 80 and finer. If you ran coarse grit belts (24-60) in the paper, the backing would wear out before the grain was fully utilized. Paper is exceptionally well-suited for belts in grits 150 finer, resulting in a finer finish per grit than cloth and will cost less.

- Belts should be at least 6-8" in width and over 150" long. Short belts like portable belts, belts for edge sanders, backstand belts or Dynafile machines are usually fairly short and narrow and therefore have less cool down time in operation. Heat is the enemy of any abrasive. These shorter belts do not provide time for the heat built up during sanding to dissipate in use and while they may at first glance appear to be less expensive, they are in fact more costly in number of belts per piece worked and downtime for belt change.

Paper can be chemically treated to be waterproof and should be marked as waterproof or with the abbreviation W/D or WP.

CLOTH

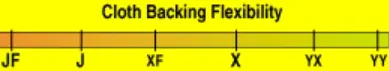

Cloth backings have three basic weights.: J, X and Y. J and X are cotton materials.

- The J has a slight degree of conformability and should be used where a small degree of conformability to the workpiece is needed in belts or sheets.

- The X is heavier weight cotton and is an all-purpose/general-purpose backing used in a various belting applications, including portable belts, intermediate belts and wide belts.

- The J and X weight backings have flexed versions available that are referred to as J-Flex (JF) and X-Flex (XF). These would be suitable for applications where the X or J is not quite flexible enough. The most common uses for JF backings are as pump sleeves and for mold sanding belts. The XF backings are used mainly for slack belt operations.

- Y backings are 100% polyester (or in some cases, a 60/40 poly/cotton split) and are used for flat, heavy-duty dimensioning, other high-heat, or rough applications.

- The Y backings are not flexed but come in a lightweight poly (YX) and a heavyweight poly (Y or YY). Normally 24-50 or 60 grits will be the heavier poly backing, and the 80-120 will be the lighter poly backing.

No cotton backings are naturally waterproof, but they may be chemically treated to be waterproof. If this has occurred, the backing should say waterproof or marked as W/D or WP. If you do not see such a marking on the back of a cotton belt, do not run with water, or the backing will stretch. You may use 100% oil as a lube if that is not detrimental to your application.

Polyester, on the other hand, is inherently waterproof. It is not chemically treated to attain this resistance, so it is not generally marked as W/P on the backing. Still, the manufacturer may note this in a product description. Any 100% polyester back is waterproof. Because polyester is naturally waterproof, shockproof, and tear resistant, it is often seen in heavy duty, rough applications and wet grinding applications.

FIBER

Fiber backings are very heavy paper backings. Several sheets of paper stock are combined using chemicals, heat, and pressure in a process called “vulcanizing”. The results are robust, heavy paper backings used for fiber discs or “vulcanized discs”. Fiber backings are not waterproof but are when used with grease sticks or 100% oils as lubricants. Many companies also offer lubricated fiber discs, which negate using grease sticks or oils as lubricants.

FILM/LATEX

You may also encounter film or latex backings. Film/latex backings are almost like a plastic paper. They provide the finishing characteristics of paper with the strength of a lightweight cloth.

We see a lot of film or latex products enabling sanders to be used incorrectly for specific applications. For instance, we commonly see people using orbital sanders to sand corners. As round objects are not meant to fit into square areas, normal paper-backed products will tear when orbitals are used in this fashion. Not only is this inappropriate use for the abrasive disc, but the pads on the sanders themselves, also being round in shape, are not meant to do this type of sanding.

Film and latex-backed discs are usually more expensive than regular paper-backed products, considering you'll have to replace backup pads for the sanders more often. At some point, the sander will need repairs involving bearing replacement; you'll eventually realize you have paid for a rather expensive convenience. Jitterbug and other sheet sanders are reasonably priced and designed to perform corner sanding while using standard paper backings. They will provide as good a finish in the same amount or less time with less upfront and hidden costs overall.

The true advantage of latex or film-backed discs lies is in their ability to produce finer finishes in the very fine grits and be used wet or dry. If you have fine, very fine finishing or wet finishing applications, the extra money paid for these backings may be justified.

BONDING

In the making process, every coated abrasive receives two layers of adhesive bonding. The first layer, referred to as the maker coat, actually adheres the grain to the backing. The second layer, referred to as the size coat, ties the individual grains together (so that they act as a unit rather than individual grains) and provides protection against heat.

In the early days, glue bonds were the only bonding agents available. These glue bonds were animal-based products that were not phenolic or thermo-setting. In other words, when they got hot during use, they re-softened. The advantage of this re-softening is that the bonding then acts like a cushion for the grain, which results in softer finishing characteristics. The downside is you lose aggressiveness of cut and life, as the protection for the grain from heat offered by phenolic resins is absent in glue bonds.

With the advent of synthetic resins, the productivity and life of abrasives were greatly enhanced. Resin bonds are phenolic and, therefore, offer the grain excellent protection from heat which in turn extends life. Most of the abrasives in use today are resin-bonded. When you do encounter glue-bonded items, they usually fall into the “finishing” category of products as that's where the workload is the lightest and the softer scratch is most important.

Summation

For every sanding/grinding job, you should be able to look at their components and determine the qualities an abrasive will need to possess to help you accomplish the job. From the grain to the backing to the type of bonding, there are reasons or should be, for each choice you make.

The goal is always to determine what is required and then get it done in the most cost effective manner possible. You'll find there are no accurate shortcuts in sanding. You can skip grits, but you will eventually sand the same amount. If you jump from 80 to 220, you will only buy two grits, but you will use double the 220 you would use AND have the time for the extra sanding required because 220 is not designed to remove an 80-grit scratch. In general, as long as you skip no more than one grit in a sanding sequence, you should not be overworking any of the grits involved. Be aware that just because things may SEEM to save you money on the front side, you will be paying in time, aggravation, or some other commodity likely just as valuable as the money on the backside.

Abrasive Grains

Aluminum Oxide - A blocky, hard grain best suited for sanding and grinding ferrous and non-ferrous metals, wood and solid surface materials.

Silicon Carbide - A sharp, complex, and brittle grain best suited for sanding glass, plastics, rubber, ceramics, solid surface materials and non-ferrous metals.

Alumina Zirconia - This tough and sharp grain works well for grinding stainless steel, spring steel, titanium, and other hard steels and for dimensioning wood.

Crocus - A natural abrasive of iron oxide particles. They are used primarily for cleaning and polishing soft metals.

Emery - An abrasive that is a natural composite of Corundum and Iron Oxide. The grains are blocky, cut slowly, and tend to polish the abraded material.

Garnet - A very sharp grain that cuts very quickly when new. Fractures quickly, keeping it sharp. Perfect for sanding wood end grains or for final-finish sanding of wood. Very economical.

Stearate - An additive that deters loading when sanding soft resinous woods, after sealer coats, and when working with soft ferrous or non-ferrous metals. Not an abrasive grain.

Abrasive Backings

CLOTH

- JF - A lightweight, very flexible Egyptian cotton cloth

- J - A lightweight, flexible Egyptian cotton cloth

- XF - A heavy, yet flexible Egyptian cotton cloth

- X - A heavy, stiff Egyptian cotton cloth

- YX - A lighter-weight polyester backing

- YY - A hefty, stiff polyester backing

FIBER

A very hard, strong, coated abrasive backing material consisting of multiple plies of chemically-impregnated paper. It is used primarily for disc products.

![]() PAPER

PAPER

- A - very lightweight paper - typically for sheet use only or light PSA or hook & loop disc usage

- B - lightweight paper - typically for sheet use only or light PSA or hook & loop disc usage

- C - medium weight paper - typically for sheet use only or light PSA or hook & loop disc usage

- D - medium to heavyweight paper - typically for sheet use only or PSA or hook & loop disc usage

- E - heavyweight paper - typically for stroke or wide belt sanding

- F - very heavyweight paper - typically for stroke or wide belt sanding